Fajalauza: Traditional Techniques in Spanish Pottery

Though Fajalauza ceramics have traveled the globe, their artisans remain faithful to the traditional crafts that their Moorish ancestors had perfected during their 600-year reign in Andalucía.

Moorish Roots of Andalusian Pottery

In the 15th century, the fall of the last reigning Muslim kingdom on the Iberian peninsula changed every aspect of Andalusian society, from religion to commerce.

Artisan at work on the potter’s wheel, 1905. Image by ARTURO CERDÁ Y RICO

As the Castilian crown expelled the Muslim population, those who did not flee had to convert and adapt. A list of local artisans from the 16th century shows that the majority of artisans in pottery still hailed from Moorish families: Alonso Alaconí, Francisco el Guadixí, Juan Valencí, among others.

Andalusian potters adapted to the new social order.

Since the new Christian settlers preferred a more temperate use of decorative ceramics, royal lusterware gave way to more modestly decorated pieces destined for the home. Production shifted to plates as meals were now eaten on individual dishes instead of following the earlier Hispano-Arab custom of sharing from a large serving bowl or aitafor.

But, some things remained the same.

The Ainadamar canal built in the 11th century still carries water. The local clay from the banks of the Beiro River is still here. And the men and women whose ancestors had plied this trade for centuries stayed.

Potter throwing pots on the wheel in 1905 (left). A 1922 Fajalauza lebrillo serving bowl (right)

Traditional Roles in a Spanish Pottery Workshop

A thriving pottery workshop requires taking care of a great variety of tasks.

The newbie or aprendiz works all over the shop: sweeping and cleaning the kilns – getting to know the place.

The rabero or oficial de raba is the jack-of-all-trades. He fetches clay from the storage to keep the potter’s wheel busy, rotates the ceramic pieces to make sure they dry properly in the sun, makes trivets to separate dishes and bowls whey they are stacked in the kiln, loads and unloads the oven and packs the finished goods. He may also know how to paint a little. He’s the grease that keeps operations running smoothly.

A rabero with serious kiln experience is an enhornador. He has the substantial task of arranging plates and bowls the kiln, a task that still requires a complex organizational scheme to make the most of each load.

The tornero is the architect. He works the wheel along with his discipline who prepares the wet clay and carries the pieces out to dry before they fire in the kiln.

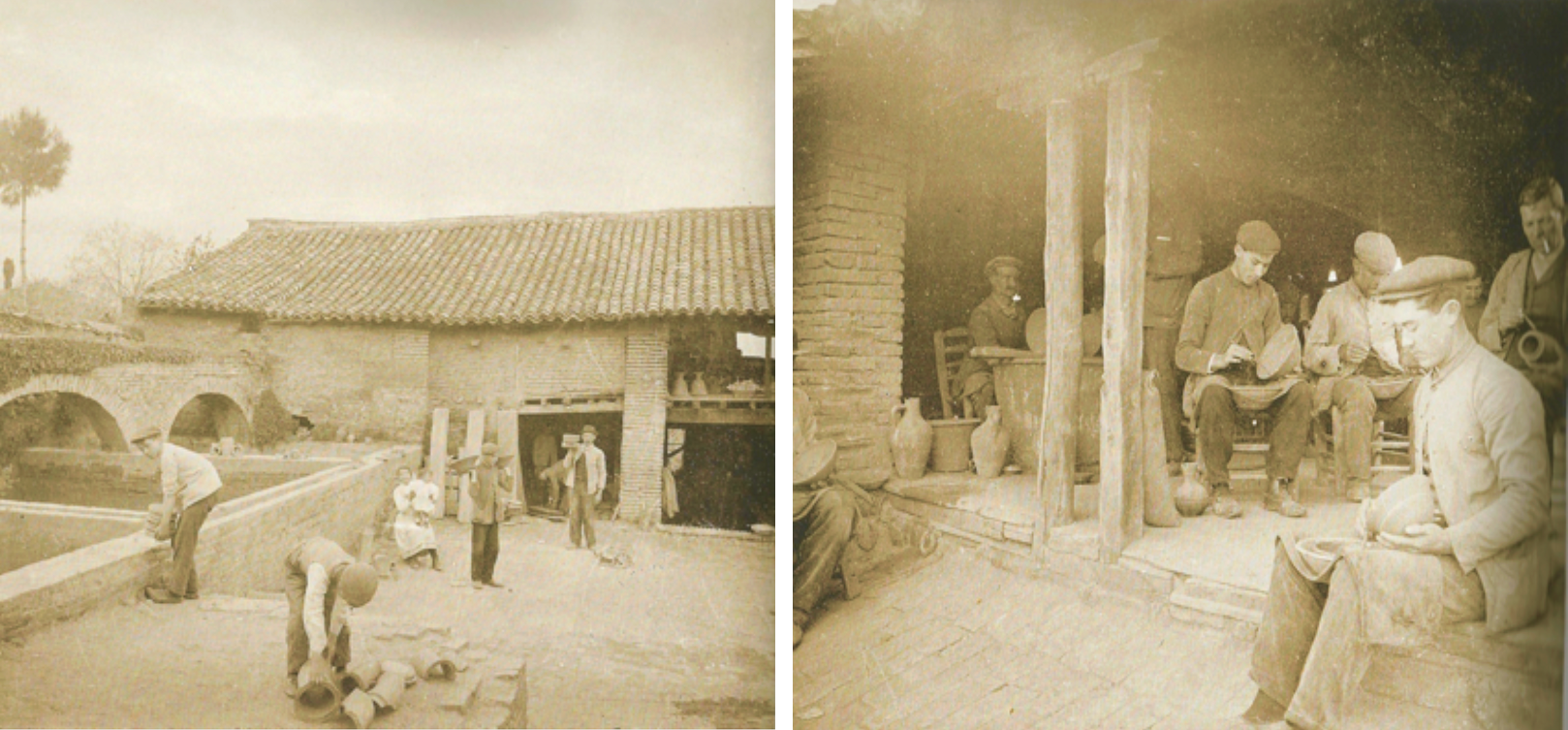

Potters and painters in a workshop, 1915. Photos by J. MARTÍNEZ RIOOBÓO

The alfarero maestro is the artist. He sits on a low chair and paints with a thick brush of horse’s hair. The earliest decorations were rather simple. Motifs usually include insects, birds, flowers, fruits, branches, geometric patterns, and inscriptions.

The maestro, a veteran artisan, has done it all. He is the technical director of operations and usually inherits the shop.

By and large, these traditional roles have been reshuffled to adapt to technological advances. For example, nowadays workshops no longer require a muleteer or arriero to transport clay from the quarry to the or deliver hay for packaging. The lumberjack who also brought firewood on the mule lost his place as electrical kilns took over.

During Spain’s Moorish era, potters fired their wares in the traditional Arab kiln. Though there are some functional Moorish kilns throughout southern Spain, most artisans make use of smaller electric kilns to fire their ceramics.

Majolica: Hand-painted Fajalauza Techniques and Motifs

Perhaps the most enduring role is that of the alfarero maestro painter.

Fajalauza decoration was and is still done by hand, one piece at a time. Using thick brush strokes, the artist applies the design in color over a tin-glazed ceramic vessel in a technique called "majolica." The master painter still handles the most important pieces while his assistant paints less complicated patterns.

Despite changing customs, archival material proves that centenarian Fajalauza motifs still charm us today. Our Manojo de Flores Lebrillo Serving Bowl is a good example.

When we compare this bowl to the 1922 lebrillo above, we can see a clear and faithful lineage. Following the classical scheme in the iconography of Granada ceramics, a central axis of symmetry organizes the decoration. A geometric pattern covers the walls while the base features a floral motif with oval petals and reticulated center. Winding foliage frames the composition in both bowls.

Fajalauza ceramics continue to favor vegetal motifs, especially the pomegranate or granada, birds and geometric patterns in bold compositions that cover the entire surface of the vessel.

Manojo de Flores and Reina Lebrillo Serving Bowls by CASA PLETÓRICA